Your turn begins with a quandary: do you venture to the collapsed coal mine and express sympathies, knowing it’ll keep you from glad-handing your supporters back home and building support for key bills? A question, in political war games, answered less by your own conscience and more by the gleam coming from across the table. Or perhaps the grin right next to you, your supposed ally getting ready to stab you in the back should you abandon London.

It’s your choice, Prime Minister.

Political war games may lack the hexes and counters of traditional war games, but they are very much flush with intricate decisions, crucial luck injections, and heaps of delicious table talk. If you’ve never ventured beyond euro comforts because chucking dice on a battlefield isn’t compelling, or if you’re looking for games driven by interaction, it might be time to try your hand at cardboard politics.

A Different Sort of Victory Points

In political war games, influence is everything. Not area control, not massive troops or resource production, but the ability to sway your fellow players (or pieces on the board) in the direction you want them to go. Versailles 1919, designed by Geoff Engelstein and Mark Herman, stands as a great introduction to this sort of game. Here, players represent nations negotiating the treaty that concluded World War One. As various elements for the treaty come up, you’ll see how important a given issue is to your country (France, for example, cares quite a bit about disarming), and you’ll have to make deals with the other players to support your interests. Maybe you’ll help Italy get back some of its northern territory in exchange for their support cutting German industry down to size. The freeform deal-making leads to on-the-table consequences, and the next time Italy’s need comes around, you might decide they’re getting a little too much and cut a deal with Britain instead. Or, if you’ve pressed your hand, and your required bad accent, too far, the other players might leave you in the cold.

leave you in the cold.

But when you’re not a threat, you’re an easy bargaining partner.

Political war games reward role play, and the best let you fall right into your character. Prime Minister, a 2023 design by Paul Hellyer, literally casts you as a singular politician in Victorian England, struggling for the unenviable position of (you guessed it) Prime Minister. The other players fill out spots in your party or the opposition, a light veneer masking the everyone-for-themselves win conditions. Pitching your back-bencher to support your bill, and making a simultaneous push to the opposition for the votes they’ll gain in the next election is good fun that turns great when your ally decides to hang at the pub and your enemies dump all their resources into tanking a law prohibiting children from working the mines.

It’s hard to laugh when someone scores a dozen points or knocks out your main fleet, but when your flagship bill crashes and burns, dooming, say, the gentry’s attempts to hoard grain? You’ll slug your pint and laugh your way to the next round’s revenge.

All this to say these games bring about a personal touch that evades pitfalls common to social deduction and party games. You’re not trying to fool or manipulate other folks. What you need’s right there in the open, but what will you trade to get it?

Historical War Games Without the War

Political war games also offer a different window into history. You’re not locked into a battle with clear sides – this isn’t Hannibal: Rome vs. Carthage — but instead a murky, messy pit of possibilities. Take Dr. Reiner Knizia’s Quo Vadis (redesigned last year by Bitewing Games into the excellent Zoo Vadis): a pure negotiation game framed around the Roman Senate. You’re pushed to make promises to other players, dealing back and forth to accomplish your ends. There’s no area control, no dice battles. Just pure deal-making, what you can offer and how much you can get from your rivals.

Similarly, 2015’s Churchill, by the prolific Mark Herman, **draws back WW2 to its headline trio, giving three players choices of how to proceed in navigating the conflict. You’ll squabble over logistics, territory, and what to do when that rascal Truman suddenly shows up. Using your staff deck to nudge issues in your favor, or steal them away from another player is both satisfying and prone to outbursts declaring your absolute need to run a clandestine op in Egypt or that your friend would doubtless blow an invasion of Japan.

Exactly, as rumor has it, Yalta went…

Cole Wehlre’s John Company (both editions) ventures away from world wars and puts your table in the shoes of outright villains, questing to exploit India in the name of the Crown and, more importantly, profit. Negotiated favors and promises are passed around like crumpets at tea as players try to swing control, cash, or a nice retirement for their uncle. Random events fertilize the chaotic ground, growing new narratives every turn as you decide where to send your haphazard family, and whether it’s worth burning the East India Company to ash just to spite your buddies.

Cole Wehlre’s John Company (both editions) ventures away from world wars and puts your table in the shoes of outright villains, questing to exploit India in the name of the Crown and, more importantly, profit. Negotiated favors and promises are passed around like crumpets at tea as players try to swing control, cash, or a nice retirement for their uncle. Random events fertilize the chaotic ground, growing new narratives every turn as you decide where to send your haphazard family, and whether it’s worth burning the East India Company to ash just to spite your buddies.

John Company and Churchill are different dances, yet both use their complexity to scaffold the history at their hearts, creating a richer experience for those players looking for it. But it’s difficult to jump right into games like these without a solid tabletop footing, as interplay demands a familiarity with the mechanisms at hand. How, after all, can you make a deal without understanding what’s at stake?

How to Get into Political War Games

Climbing the hobby’s complexity ladder is neither required to enjoy board gaming nor worth doing just for its own sake. Instead, if you’ve sprinted through another round of Ark Nova or Brass, and found yourself itching for something more interactive, more focused on things beyond victory points, then it might be time to take a look at the games I’ve mentioned above.

I choose Brass and Ark Nova as comparisons because neither is an introductory game: political war games are best tackled by those willing to digest their considerable rulebooks, their oft-different board setups. Of course, if you’re a crew of hardened Twilight Imperium or War Room junkies, then dive right in.

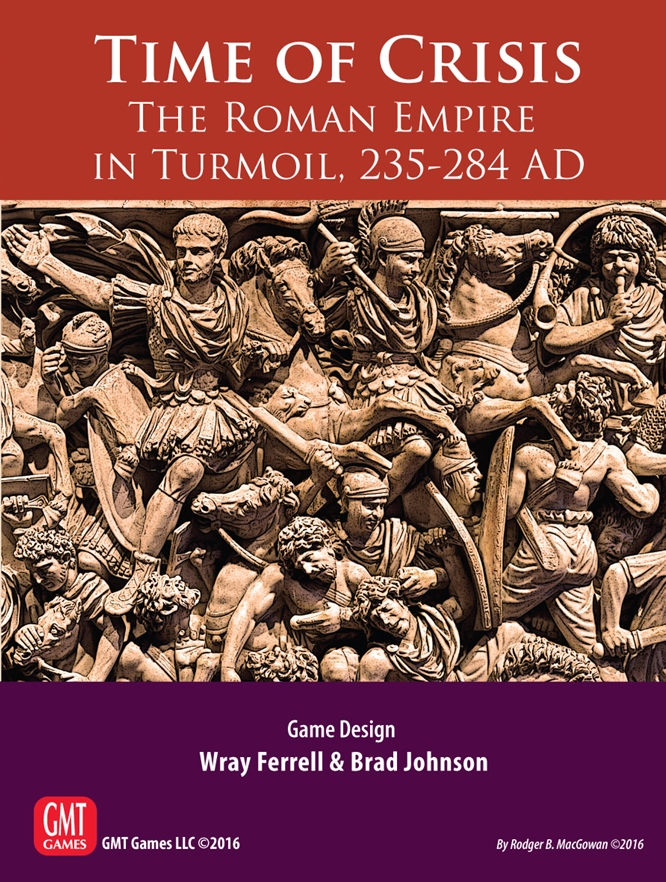

Once you’re ready, seek your entry point. Does your group find the Roman Empire fascinating? Then Time of Crisis: The Roman Empire in Turmoil might be your ticket. Lovers of science fiction might start with Sidereal Confluence or Stationfall. There are countless Renaissance, Victorian, and modern-era versions,

Once you’re ready, seek your entry point. Does your group find the Roman Empire fascinating? Then Time of Crisis: The Roman Empire in Turmoil might be your ticket. Lovers of science fiction might start with Sidereal Confluence or Stationfall. There are countless Renaissance, Victorian, and modern-era versions, like Tammany Hall, Imperial (and its sequel, Imperial 2030), and others.

like Tammany Hall, Imperial (and its sequel, Imperial 2030), and others.

Then, once you and your group have learned to sling your words as well as any dice-driven weapon, you’ll be well-equipped to jump into some absolute, day-dominating classics.

Here I Stand, Virgin Queen, and last year’s Europa Universalis: The Price of Power combine the savvy diplomacy and role play of political war games with their more combat-oriented counterparts to make massive experiences. These are games that, with the right group, get talked about for years to come. Provided, of course, you have supplies of caffeine, snacks, and concentration at hand.

But if you do, mark off a Saturday with your group, send out a how-to-play video beforehand, and get ready for something special.

Games that Tell a Tale

A beautiful thing about board gaming is its variety. Political war games are another special avenue we get to explore, one that will challenge you to play as much with your friends (and enemies) as solve a puzzle.

Putting on Winston’s Homburg hat or donning Caesar’s toga, perhaps in metaphor only, and inhabiting their struggles, fighting for their goals, is an immersive experience, one that transcends a simple win or loss to tell that most valuable thing we gain from gaming together: a story.